Advancing The Worst Supply Chain in North America

First, kudos to Steve Banker for having the courage to write and publish what many of us in the oilfield services and upstream oil and gas sector have, at best, only whispered quietly to each other. While the industry has had spectacular achievements, applying technology to extract oil and gas from rocks buried thousands of feet in the earth, the supply chains that support the effort seem dysfunctional, immature and inefficient, even to many veterans of the oil patch.

We agree with the author that, “the industry does attain fairly high service levels” and that those high service levels are necessary given the economics of well construction and maintaining oil and gas production. Sadly, we also agree that the achievement has more to do with brute force rather than finesse or supply chain science. Participants in the supply chain have put in place multiple layers of inventory to support the high service levels required by their customers in the face of unpredictable demand and long lead times. While each player has worked diligently to optimize their own piece of the supply chain, when you put all the suboptimal pieces together, the result may very well be “The Worst Supply Chain in North America.”

Us and Them

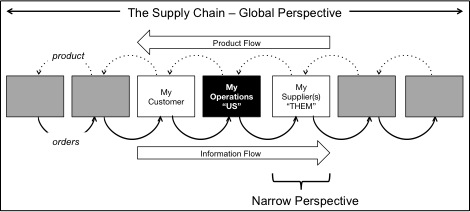

Our poor performance is due, in part, to a very real lack of affinity between the players in the supply chain. Many participants, from the oil and gas company to the service company to their suppliers, views the supply chain as having two pieces, dividing their view of the supply chain into “us” and “them.” Mutual trust is low and communication is therefore guarded. Due dates are padded to compensate for uncertainty in demand and unreliability of delivery. “Just-in-case” inventory becomes the dominant fulfillment strategy. Customers demand pricing concessions but do not recognize the need to share the forecast with their suppliers – sharing that information would help their suppliers operate more efficiently and lower costs. Suppliers react to the pricing pressure with service-endangering cost cutting to preserve their margins. Every player in the supply chain is “optimized” but overall, the extended supply chain fails to deliver.

The Customer-Anchored Supply Chain

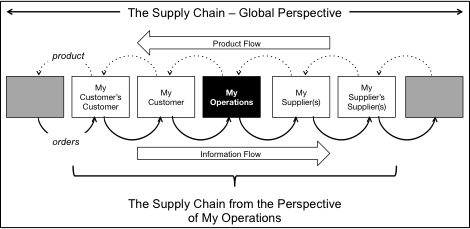

We believe the only real solution for the industry is to break the paradigm of “us and them.” Each participant – E&P company, oilfield service company and supplier – must “own” the total supply chain. Individually, we each must recognize that the supply chain that we “own” includes our customer’s customer and our supplier’s supplier (see APICS SCC SCOR model). When we do this, we will find that our goals will align with our immediate customer – we will both strive to satisfy the same customer. Consider, for example, the potato chip manufacturer. Their customer is the grocery store and their customer’s customer is the consumer. By recognizing their customer’s customer is the consumer, the potato chip manufacturer aligns goals with the grocery store. There is alignment because both the potato chip manufacturer and the grocery store want us, the consumers, to buy their potato chips. That is why the manufacturer provides ways to increase demand with sales and promotions in the store. Likewise, in the oil patch, each participant in the supply chain must anchor themselves in their customer’s customer to drive supply chain excellence.

Similarly, if each participant in the OFS supply chain aligns with their suppliers and their supplier’s supplier we would recognize the need to share forecasts – forecasts that would drive S&OP processes across the supply chain and start to build a more efficient and effective industry supply chain model. With this model comes an opportunity to lower costs, lower prices and maintain or improve margins. For each participant the path from the worst to the best supply chain starts with implementing a Customer-Anchored Supply Chain©.